Recent articles have alluded to the potential benefits from the integration of technology into multiple areas of the criminal legal system. Winston Churchill wrote, “Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” He may have altered the original phrase attributed to the Spanish philosopher George Santayana “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” For the purposes of this article I will go with Churchill’s version.

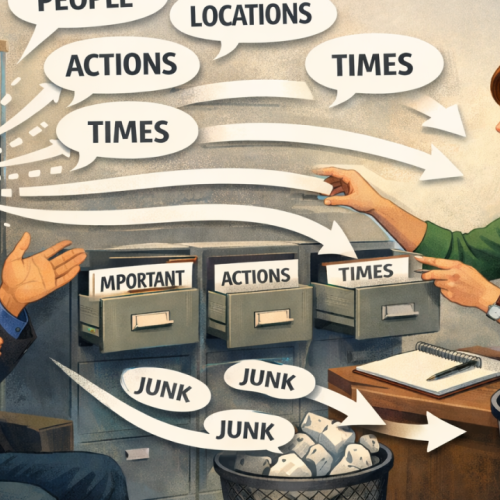

The often-stated goal for an investigative interview is the complete, accurate, and reliable account of the matter at hand. The barriers to this goal tend to be, using a jigsaw puzzle analogy, we rarely if ever have all the pieces, so any account will lack some details and will not be 100% complete. Accuracy relies on the perspective of the beholder; memory is inherently malleable and therefore needs corroboration (if available). Reliability may be considered as the concept that the information gathered “will stand up to scrutiny and examination” and thus be sufficient for use in any proceedings. If we now add AI in the form of LLM’s into this mix, we have the potential for some significant issues.

For an example of how wrong the unbridled use and reliance on technology married with a lack of ethical and fact gathering investigation can be, the reader should take a deep dive into a series of cases in the UK collectively labelled “The Post Office Scandal” the circumstances of this “scandal” offer a profound warning about the dangers of unregulated technological systems in the justice process. Between 1999 and 2019, hundreds of innocent sub-postmasters were wrongly prosecuted because the Post Office treated data produced by its Horizon computer system as inherently trustworthy. Courts accepted this digital evidence without question, despite repeated system failures, withheld disclosures, and known software errors. The scandal demonstrates how digital opacity, institutional incentives, and systemic ignorance can align to impact lives and why similar dangers may present themselves with the rapid, uncritical adoption of AI based systems in the criminal legal system.

At the heart of the Post Ofice investigation was a misplaced presumption that the Horizon computer system employed by the postmasters was accurate. Judges and lawyers routinely accepted computer-generated figures as factual truth, without demanding proof of reliability or technical validation. As a UK barrister notes, “It was taken as given that what a computer record showed was correct. The shallowness of this approach is reprehensible.”

If this sounds implausible, research has demonstrated that when presented with judgements made by a computer, a human will often defer to the decision made by the computer. The study - Lie Detection Algorithms Disrupt the Social Dynamics of Accusation Behavior (von Schenk et al., (2024) highlights how the presence of algorithmic lie detection influences human judgment, particularly our inclination to accuse others of deception. At its core, the research reveals a significant psychological shift: when people actively choose to consult a lie-detection algorithm, they overwhelmingly defer to its judgment especially when it suggests that someone is lying. Notably, individuals who would not otherwise make accusations become substantially more likely to do so when supported by algorithmic predictions.

The findings suggest that humans may default to machine judgment not necessarily because they are more prone to accuse, but because the machine’s presence lowers the perceived cost or social risk of making a false accusation. This deference is especially pronounced when individuals initiate the request for the algorithm’s opinion, reflecting a possible overreliance on technological authority in assessing veracity even in morally charged situations.

At the time of the Post Office investigation, previously enforced statutory safeguards that once required proof that a computer was functioning properly before its output could be used as evidence had been removed. This created a legal vacuum where technological evidence was presumed reliable, a presumption now migrating into AI-driven risk assessments, predictive policing tools, and automated evidence analysis. As with Horizon, AI models can embed undisclosed errors, biases, and algorithmic opacity that remain undetected unless courts and defense teams have both access and the expertise to challenge them.

The Post Office used its near-unlimited resources, backed by the government, to suppress evidence of Horizon’s defects. It resisted disclosure of the Fujitsu “Known Error Log” for years, even denying its existence. Multiple judges accepted these positions, and individual defendants lacked the means to obtain expert analysis. This pattern demonstrates how institutional actors can weaponize information asymmetry to defeat accountability.

In the context of AI systems, such asymmetry is magnified. Proprietary algorithms are often protected by intellectual property law or trade secrecy. When these systems influence charging, sentencing, or parole decisions, defendants especially those without resources face the same structural disadvantage as the postmasters: they cannot meaningfully contest the validity of the digital evidence shaping their fate.

The scandal was compounded by ethical failures across corporate and legal institutions. The Post Office concealed known system bugs (such as the “Receipts and Payments mismatch” bug) even while its expert witnesses assured courts that Horizon was reliable. Lawyers and executives knowingly allowed prosecutions to proceed on false premises. When independent investigators, such as Second Sight Ltd, began uncovering evidence of systemic flaws, the Post Office terminated their engagement and misled Parliament about its reasons.

AI-driven justice systems risk similar opacity and abuse. Without mandatory transparency and independent auditing, agencies deploying AI tools may suppress or spin unfavorable findings. The economic and political incentives to protect institutional reputation, as with the Post Office, will outweigh incentives for disclosure, especially when AI systems are marketed as objective or efficient.

The Post Office scandal was not a technological failure alone; it was a human, ethical, and institutional collapse amplified by misplaced faith in machines. As courts, police, and prosecutors now turn to AI for decision-making, the parallels are stark. A blindness to error, resistance to disclosure, and imbalance of power that shielded Horizon’s flaws could make algorithmic injustice even harder to detect. The lesson is clear: no algorithm should be trusted merely because it is digital. The principles of investigative interviewing must remain throughout any investigation. The ethical interviewing of witnesses and those accused should remain at the heart of any inquiry with the investigator seeking to obtain complete, accurate and reliable information on the matter at hand. However, exploitation of ignorance can be valuable. St Thomas Aquinas postulated a moral dilemma in a commercial situation. A merchant on a sailing vessel arrived at an island with cargo that the islanders had not received for many months. The cargo was accordingly very valuable in the market. What if the merchant knew that coming behind them was a large number of ships laden with similar cargo? Are they morally obliged to tell the islanders, or should they exploit their ignorance by maintaining a high price? What the dilemma illustrates is that ignorance has value. In law there are a large number of circumstances where the imperative to take advantage of ignorance is powerful. There is a line that can be crossed. Ethics can be expensive.

The Post Office Horizon scandal and inclusion of AI systems into any investigation process such as the axion report writing system expose the same structural vulnerability: the uncritical deference to technology as a source of truth. In Horizon, this led to wrongful convictions because computer outputs were accepted as infallible evidence. In the Axon system, the danger lies earlier in the evidentiary chain, the formation of the record itself.

In both cases, the machine becomes a co-author of the human narrative, eroding epistemic integrity. Once a technological system generates a confident account, human actors even judges, officers, or jurors-tend to anchor their beliefs around it, even in the face of uncertainty. The result is a self-reinforcing cycle of credibility that resists correction unless immense external scrutiny is applied.