Word of the Day - Circumlocution

Definition - the use of many words where fewer would do, especially in a deliberate attempt to be vague or evasive

Investigative interviewing is designed to obtain a complete accurate and reliable account from the person being interviewed. (Ask & Fahsing, 2018). But the devil is often in the details.

As interviewers we as we look for detail, we may make judgements about people based on, just how much they talk. It turns out that this one simple thing can completely and often incorrectly shape how we see them, their character, how cooperative they are, and even whether they're guilty or innocent.

In two separate interviews, one interviewee gives you short, to the point answers. The second interviewee is really chatty, maybe even rambling a little. Which one makes you suspicious? Research has shown that truth tellers generally provide more details than lie tellers. In addition, lie tellers tend to skip details because of cognitive load and the difficulty to keep their stories straight. (Hartwig et al., 2006)

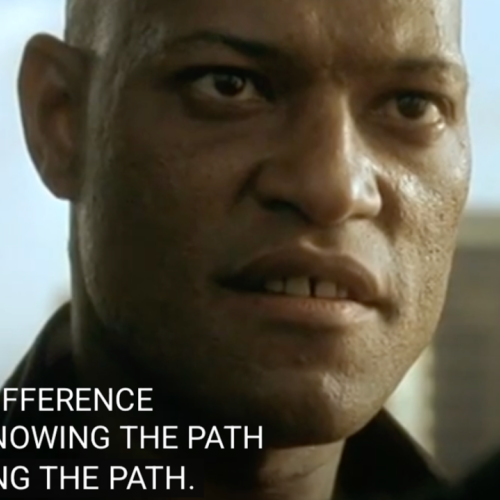

However, interesting new research suggests those instincts could be leading you completely astray. For decades, investigative interviews have been built on a straightforward, almost common-sense idea that if you build a good rapport with someone, they'll open up. Some training can lead Interviewers to think that a long, detailed responses are a win, it's a sign that the person is cooperating, that they're giving you information. More information must equal higher probability of truthfulness. But in (Weiher et al., 2025) there is a big counter idea. What if being super talkative isn't about being cooperative at all? What if it's actually a strategy? Their research found that a guilty person might just drown you in a sea of words, irrelevant stories, random opinions, details you can't possibly check. Designed to create this facade of honesty while they carefully dance around anything that actually matters.

These researchers came up with an experiment to figure out the exact impact of someone's word count on how we judge them. Essentially, they set up a mock police interview for a burglary. A key element was that the evidence against the suspect was strong, and it was identical for every single person in the experiment. Objectively, this person looked pretty guilty. Participants listened to one of three different interview recordings. In the low verbosity one, the suspect gives short direct answers. But in the medium and high versions, the suspect adds all this extra, totally irrelevant information. The core answer, it never changes. It just gets padded with this conversational fluff. Key factor was that the facts of the case were always the same. The questions were identical. The only thing that was different was how many words the suspect used. Analysis of the results uncovered a powerful cognitive bias that probably reflects how we all judge people every single day.

Isolating rapport, described as the connection that listeners felt between the suspect and the interviewer. The results were crystal clear. The more the suspect talked, the better people thought the rapport was. The quiet suspect seemed distant, while the chatty ones seemed like they were really hitting it off with the interviewer. But the concurrent effect observed was that as the suspect talked the more their perceived guilt went down.

This was despite the evidence in each case was exactly the same. The results showed the observers thought the most talkative suspect was way less likely to be guilty than the quiet one. Just by adding meaningless words, the suspect actually seemed more innocent. This was named by the researchers as the verbosity bias.

The possible explanation was that the brain was taking a mental shortcut. The observers were not differentiating between quantity of words with the quality of information, which may induce us to think talkative people are more cooperative and less guilty. Despite the objective facts being identical. It means that this manipulative tactic, just adding filler to the answers to seem cooperative, can actually have an effect. It can fool people into believing someone is innocent, even when all the evidence is pointing the other way.

But the findings of the research did not stop there. Because there was a fascinating exception to the rule, they identified a group of people who, were less susceptible to this effect. As they were looking through their data, the researchers noticed that about 22% of their participants, identified as neurodivergent. This can include conditions like ADHD, autism, or dyslexia. With this information they decided to run the numbers again just to see if this group reacted any differently. And this result was remarkable. the neurotypical listeners displayed the identified verbosity bias. More talk equaled less guilt. However, for the neurodivergent listeners the bias just disappeared. It appeared that for neurodivergent listeners, word count just wasn't a factor. They didn't connect being chatty with being less guilty at all. The researchers developed a theory. They suggested that neurodivergent individuals might be more wired to focus on the hard data, the actual factual evidence in the case. rather than getting swayed by social cues like how chatty someone is. That their tendency to focus on detail might have acted like a shield against this bias. The study's authors argue for a big shift in how we approach information versus detail. Instead of training interviewers to chase the generating information as some sign of good rapport, the focus really needs to be on the details of the information obtained. Is the information verifiable, and is it even relevant?

A potential solution. When conducting interviews, investigators face the difficult job of having to actively listen, process the information and then come up with questions all while taking notes simultaneously. The use of a linear structure of taking notes, where interviewers try and make a written record of all the information provided by the interviewee, raises the cognitive load on the interviewer. In fact, an interviewer’s information processing systems are likely to be overloaded (Kolk et al., 2002)

During the course of an investigative interview the interviewer is expected to gather relevant information for the purpose of some future proceedings. Defining what exactly that information is often not clear. Mostly it has been gleaned by experience or the passed down institutional knowledge of a respected colleague. A system of note taking was developed in the UK which defines detail and provides the distinction between the all important evidential detail from the important investigative detail. The Notetaker system was developed by Kerry Marlow as a way to provide a consistent approach to the gathering of detail. (Marlow, K.M 2002)

The use of a structured note taking system potentially addresses the verbosity bias identified in (Weiher et al., 2025). The Notetaker system is designed improve the quality of the information gathered and facilitate subsequent analysis. It represents a methodical way for investigators to gather information during interviews. This system also allows an investigator to record accurate notes during an interview and differentiate between evidential and investigative detail. This focus on 4 categories of information people, locations, actions and times (P.L.A.T) may invite the neurotypical investigator to act in a similar manner to the neurodiverse investigator by focussing on the detail, the actual factual evidence in the case. rather than a lot of words from the interviewee. but who is saying nothing of value it acts like a shield against this bias.